Peter Korotaev

A farmer on his farmland in Western Ukraine. Image credit: CGTN.

A farmer on his farmland in Western Ukraine. Image credit: CGTN.

Part I: Ukraine’s Privatized Agriculture: A Hungry Guarantor of Global Food Security

Former Canadian ambassador to Ukraine Roman Waschuk said Ukraine is a country where the IMF does ‘economic experiments’. Ukraine is a laboratory for testing radical neo-liberal policies, irrespective of the harm ordinary Ukrainians face from them.

Of Ukraine’s 60 million hectares of land, 55 per cent (33 million ha) is considered arable – the highest such figure in Europe. Some more optimistic estimates place that figure at 74 per cent. The world average is 12.6 per cent. 2.3 per cent of the world’s arable land is in Ukraine. Much is often said of Ukraine as the ‘breadbasket of Europe’ – indeed, Ukraine’s arable land accounts for 25 per cent of Europe’s.

Things aren’t so rosy when it comes to Ukraine’s capitalist, privatized agriculture. While it exports plenty of sunflower oil and corn, food production has plummeted for decades, the land is monopolized by big agroholdings, the quality of the land is rapidly dropping because of unsustainable agroholding practices, and the population suffers from equal or worse levels of hunger as countries in Latin America.

The power of big agroholdings – Ukraine’s agricultural relations

In the 1990s, there was a privatization of the soviet state farm system. But in 2001, a moratorium was declared on the buying or selling of agricultural land. As a result, most Ukrainian agricultural land is still owned by small farmers. These small farmers numbered almost 7 million in 2019, or a sixth of the population. The remaining agricultural land is owned by the government.

The moratorium was introduced because many Ukrainian peasants were worried about losing their land to big business, especially to foreigners. Contrary to the urgings of domestic and foreign ‘market reformers’, most Ukraine’s peasants have no interest in privatizing their land. A 2005 survey showed that 96 per cent of Ukraine’s farmers did not want to start individual farming. A USAID poll conducted in 2015 showed that only eight per cent of landowners wished to sell it in the first year after the lifting of the moratorium, and a 2017 poll done by the institute of agrarian economics showed that only 10 per cent of landowners wanted to sell their land.

Until July 1, 2021, Ukrainian land could not be bought, but only rented. Due to the poverty of Ukrainian peasants, most (56 per cent) are forced to rent out their small plots to private companies. Another 29 per cent work the land themselves, 8 per cent rent it out to the government, and 7 per cent do nothing with their land. Many rent to larger companies – agroholdings. Land belonging to the government is also often rented out to big agroholdings. As a result, these agroholdings have played a dominant role in Ukraine’s capitalist agriculture.

The scale of agroholdings

The main Ukrainian agrobusiness web portal is fittingly called ‘latifundist’. Not only are Ukrainian agricultural relations often compared to those in Latin America, but Ukraine actually tops world figures in this respect.

Ukrainian largest agroholdings are very powerful. In 2017, two of Ukraine’s agroholdings were in the global top 20 list as ranked by amount of land controlled. NCH Capital, which evenly distributes its land in Russia and Ukraine, is in the top 10. Ukraine’s largest agroholding, Kernel, controlled 510 000 hectares of land in 2021. Kernel was planning to increase that to 700 000 after the ‘good news’ about Zelensky’s 2020 lifting of the moratorium on selling agricultural land. Kernel received $643 million of gross profit in the 2021 financial year, 5.2 times more than what it received in the previous year. This company alone is responsible for 22 per cent of Ukraine’s sunflower oil exports, 20 per cent of Ukraine’s grain exports, and close to 10 per cent of Ukraine’s total grain exports. Agroholdings were responsible for 22 per cent of Ukraine’s total agricultural production in 2017, though as we will see later, they have little to do with Ukraine’s food security.

It is hard to say how much Ukrainian land is controlled by large agroholdings, both because of non-transparency of these rental relations of control (relatively little Ukrainian land has been sold since the lifting of the moratorium) and the rapidly changing state of the sector. In its 2020 report, Land Matrix recorded 242 land deals (this includes rental and lease agreements) in Ukraine, leading to a total size of 3.24 million hectares under contractual control by agroholdings. This amounts to 7.6 per cent of all agricultural land and 10 per cent of all arable land.

But as Land Matrix itself admits, this is an underestimate since it only considers transparent deals.

According to ‘Latifundist’, in 2021, the top 117 agroholdings in Ukraine directly controlled 6.45 million hectares of land, which is 16 per cent of all agricultural land, and 20 per cent of all arable land. In 2020, according to ‘Eco-action’ and the Institute of Geography of Ukraine, only the top 10 agroholdings controlled 2.66 million hectares of arable land. According to the influential agrobusiness news portal ‘Landlord’, 45 agroholdings control 4.1 million hectares of arable land, with a total revenue of $10.8 billion USD.

By comparison, no EU countries apart from Romania (not coincidentally one of the EU’s poorest members) have large agroholdings. In most countries, such as Germany, no single individual or company owns more than 30 000 hectares of land, while the average size of agricultural plots is 20 hectares. Due to the negative social, economic and ecological effects of domination of agriculture by large agroholdings, only poor, imperialized countries in South America, Asia and Africa have agroholdings comparable to those in Ukraine[1].

How much land do foreign agroholdings control?

According to Land Matrix’s 2021 report, Ukraine is second on the global list of the amount of land owned by foreigners – three million hectares. Only beaten by Indonesia, Ukraine was followed by Russia, Papua New Guinea and Brazil. Another study found that 15 per cent of Ukraine’s agricultural land is owned by foreigners, or almost 20 per cent of arable land.

However, these figures are likely an underestimate. Latifundist writes that only 10 foreign agroholdings control two to three million hectares. The largest were US companies – the biggest two controlled 300 000 and 195 000 hectares. One of the ways that foreign businesses get around restrictions on owning land in Ukraine is by buying it as collateral from a Ukrainian bank. This method has also hugely discounted Ukrainian land through the use of the western program ‘Prozorro’, which we will detail in our last article.

Another reason why foreigners own more than it seems is given by Ukrainian economic journalist Roman Gubrienko. He writes that 60-70 per cent of the land controlled by agroholdings is actually foreign owned, albeit with a token Ukrainian front. A 2023 report on Ukraine’s agriculture found that nine out of ten of Kernel’s top shareholders are European or American. Ukraine’s fourth largest investor in 2020 was Norway’s Sovereign Wealth fund, which owns shares in both Kernel and its competitor agroholding MHP. Blackrock and Goldman Sachs are some of the other big global financial groups heavily involved in Ukraine’s agriculture.

Indirect relations of control by agroholdings

It is also misleading to only take into account direct juridical control over land through rental contracts. This does not take into account the indirect control over agricultural produce effected by the domination by big agroholdings of agricultural capital goods. While financially out of reach of the poor individual farmers that nominally own most Ukrainian land, big agroholdings own most processing, logistics, elevator and storage equipment. Without the appropriate equipment, peasants are forced to sell their produce for very low prices. Since trading companies and agroholdings own two thirds of all agricultural elevator equipment, they can easily force smaller peasants to sell them produce for low prices, then resell it abroad for higher prices.

Kernel is not only the biggest agroholding but also the biggest trader of agricultural produce – it was responsible for delivering 13 per cent of all Ukraine’s grain exports in 2019-20. The top three traders were responsible for delivering 30 per cent of Ukraine’s exports. The top five private owners of elevators control a third of all elevators. Kernel is also the biggest private owner of elevators. This means that in some regions, agroholdings such as Kernel enjoy a monopoly on elevators.

As a result, agroholdings can dictate prices to smaller peasants, and in reality, control far more of the agricultural industry than indicated by the land they legally control. These indirect means of control are why Natalia Mamonova, an academic specialized on the topic, wrote in 2015 that 60 per cent of Ukrainian agricultural land is controlled by big agrobusiness.

Privileged giants

The agroholdings have political power to match their economic strength. Through their lobby, the ‘Ukrainian Club of Agrarian Business’ (UCAB), they advocate for laws that raise taxes on small farmers. While the similar law 3131 failed to pass through parliament (Verkhovna Rada – VR), law 5600 was approved by president Zelensky in December 2021. This law involved increasing the tax burden on small and medium farmers. The VR expert committee critiqued the law, arguing that it ignores the seasonal specificities of various forms of agriculture and that it is based on the unproven assumption that small farmers avoid paying taxes.

According to the VR expert committee:

‘increased tax pressure on small producers may lead to the sale or lease of land by them (which may be one of the negative consequences of the adoption of the project) and lead to an increase in unemployment in rural areas, an outflow of labor to cities and abroad, a decrease in competition and monopolization of agricultural production, changing the structure of agricultural production, the commodity structure of export-import, increasing the price offer in the domestic agri-food market, etc’

The government made agricultural liberalization its top priority, regularly describing the 2020 privatization of land as one of its greatest achievements. As Zelensky put it in a 2020 pathos-laden speech to farmers (where he promised meagre credits), ‘without land reform, we have no chance to become the breadbasket of Europe’. The head of the Servant of the People party, David Arakhamia, sung praises to law 5600, pushing parliament hard to ratify it as soon as possible, despite expert critique. Taras Vysotsky, Deputy Minister of Economic Development, Trade and Agriculture and a top advocate of market reforms, was general director of UCAB until 2019.

It is hence no surprise that while the government implements laws impoverishing Ukraine’s 2.3 million small or medium farmers, it approves huge subsidies for big agroholdings. In January-September 2017, Ukraine’s largest poultry agroholding and third largest landowner, MHP (belonging to Yury Kosyuk), received 1.25 billion hryvnias in ‘agrarian support’ subsidies from the Ukrainian budget. By comparison, the 2017 budget involved 1 trillion hryvnias in spending. Kosyuk was also an advisor to then-president of the time Poroshenko, and the sixth richest Ukrainian ($900 million). Independent journalists also found that Kosyuk was a key intermediary figure in immense Donbass smuggling schemes linking US diplomat Kurt Volker and Poroshenko. The company, like any agroholding and most Ukrainian big business, has its headquarters in Cyprus (previously in Luxemburg). That means that not only does it receive enormous budget subsidies, but it evades taxes. In 2019, the company announced that it would make new investments in the Balkans and Saudi Arabia instead of in Ukraine.

MHP received $230 million USD (6.2 billion hryvnia) in pure profits in 2017. In 2018, Kosyuk’s company received 25 per cent of all state agricultural subsidies, 970 million hryvnia. In 2018, the government approved a law giving big agroholdings (before this was only possible for small farmers) the right to receive compensation from the government for credit interest.

The second most privileged company was UkrLandFarming, which owns the second largest amount of agricultural land after Kernel); receiving 444 million hryvnias. This company and MHP combined received half of all agrarian subsidies in 2017. The same year, according to state statistics, MHP received 1.8 billion hryvnia in subsidies. Two companies belonging to members of Poroshenko’s parliamentary bloc received a total of 3.5 million hryvnias, the same amount of money spent on the modernization of the streetlights of the entire city of Khmelnytsky. 60 milion hryvnia were also received for the agricultural business of a deputy of the Verkhovna Rada belonging to the parliament’s Agrarian Committee .Even the pro-western ‘radiosvoboda’ who conducted this investigation reported that it is possible that the real numbers are higher.

Apart from state subsidies to Poroshenko allies like Kosyuk, avoiding taxation is itself a form of subsidy. And this is exactly what Zelensky legislated in 2021, signing off a reduction in value-added taxes from 20 per cent to 14 per cent for imports and exports of a variety of top agricultural exports, including agroholding favorites corn, sunflower, and wheat.

Ukraine’s agrobusiness is very low down the list of top Ukrainian taxpayers, a list which itself is hardly full of high performers. The top agricultural tax payer is Kernel, which was still only at 147th place in 2020. It paid only $18 million in taxes in 2018. The same year, Kernel earned $513 million USD in profit, and its owner was among Ukraine’s top 20 richest men. MHP paid even less.

According to the NGO Ukrainian Agrarian Association, only a fifth of designated state assistance to small-scale farmers reached its destination in 2018, for a total of merely $7.4 million USD. The World Bank gave only $5.4 million in support to small Ukrainian farmers. Even this small amount did not come from the WB itself, as is the case for its loans to big agrobusiness, but required small farmers to use their future harvests as collateral to receive capital. It and other western financial institutions have found it much more important to push for the agricultural liberalization which destroys small farmers and encourages the growth of big agroholdings. We will look closer at the role of western financial institutions in encouraging the rise of big agrobusiness at the cost of smaller farmers in the final article of this series.

Analysts of Ukraine’s agricultural relations have also noted how difficult it is for smaller farmers to receive credit. Banks mainly work with clients that own over 500 hectares of land, and require extensive paperwork, as well as generally being short-term and involving high interest rates.

The decline of agricultural employment

The post-Soviet period has seen a steady decline in the amount of agricultural land controlled by family farmers. This is because the defunct Soviet Union provided large subsidies to peasants, buying much of their produce and organizing other aspects of production. The world bank, on the other hand, stated that the key to development of Ukrainian agriculture through privatization is ‘expansion of producers with higher productivity and incentives for lower productivity producers to improve or exit, as the price of land rises.’.

The more that agricultural relations has been liberalized, the more rural employment has declined. Slightly rising from 2012-13, it drastically fell from 3.3 million to 3 million in 2013-14. Declining every year since, by 2021 only 2.69 million people were employed in agriculture. It is hence no surprise that most Ukrainian farmers have consistently stated their unwillingness to become individual, capitalist farmers.

Kernel, Ukraine’s biggest agroholding, controls 500 000 hectares of land, about 1.5 per cent of Ukraine’s arable land, but only employs 15 000 workers. That means that if all Ukraine’s arable land were used by agroholdings similar to Kernel, only 990 000 workers would be needed. Given the fact that agroholdings employ quite few people, the decline in agricultural employment is certainly thanks to increased unemployment among individual farmers. While total employment fell, from 2014 to 2021 Ukraine increased annual exports of agroholding favorite sunflower oil from 12 million to 16 million tons.

The controversial privatization of agricultural land

Unpopular reforms

The marketization of Ukrainian agriculture has always been very unpopular. According to one 2020 poll, only 15 per cent of Ukrainians supported the privatization of agricultural land. Nevertheless, under cover of Covid quarantine restrictions on public meetings, during the same year, Zelensky lifted the moratorium on the buying and selling of agricultural land. Zelensky never ceases to remind western state audiences of this act to prove his credentials as a ‘defender of free market democracy’. It is well known and readily admitted by pro-privatization Ukrainian outlets that the lifting of the moratorium was due to IMF pressure.

The aforementioned makes it difficult to describe the lifting of the moratorium as particularly ‘democratic’. On the topic of democracy, Kernel has been accused of ‘raider’ captures of land, whereby they threaten or otherwise force small farmers to sign over the rights to their land. In 2016, 7150 cases of raider captures of agricultural land were recorded.

Roman Leschenko, minister of agrarian policy and food, had much to say about the necessity of land reform. While claiming that Ukrainians were ‘intimidated and misled’ into opposing the privatization of agricultural land, he was very pleased by the ‘historic’ decision to privatize the land in 2020. But he lamented that this law remained ‘highly conservative’. What he meant by this was the fact that the 2020 law did not allow foreigners to buy land – this question would be decided on no earlier than 2024.

But Ukrainian journalist Roman Gubrienko brought up the fact that several months later, there was an amendment to the law allowing foreigners to buy the land through using it as banking collateral. Even the most unpopular part of agricultural land reform – allowing foreigners to buy land is opposed by 81 per cent of Ukrainians – thereby went through quite easily, despite Leschenko’s fears. Even without the loophole, foreigners still had fairly easy access to the land – companies with US, Saudi, and European companies control millions of acres.

The price of land

In 2020, Ukrainian economy minister Taras Vysotsky predicted that the average price per hectare of Ukrainian land would be between $1480-$2224. But quite different estimates emerged from various government figures, ranging from $1000-$2500 per hectare. Vysotsky also ‘predicted’, or threatened as Ukrainian journalist Gubrienko puts it, that the price of land will fall from $2200 to $1500 if there are ‘restrictions’ on the privatization process, such as on the size of land per owner or on foreign investors. Meanwhile, all these predictions are very far from the minimal price of $8000-$10,000 per hectare of Polish land, which had been used for years to tempt Ukrainian farmers to agree to privatization. Land in western European countries costs $30,000-$64,000 per hectare.

In January 2020, Gubrienko predicted that land would be sold for even cheaper. He based this off poll results from 2019 which showed that Ukrainian land generally earns about $130 a month for its owners. As a result, he predicted prices at best of $1000-$1200 per hectare. Gubrienko predicted that the increase in supply of land would further drive down the price. The state also owns 7-10 million hectares of agricultural land and stated that it plans to receive over $1 billion from land sales in 2020. The difficulty of securing credit in Ukraine due to harsh IMF banking reforms is cited by him as another factor driving down land prices. The low quality of Ukrainian soil is another factor, itself a result of intensive cultivation of monocrops by agroholdings.

In the first three months after the land market was opened, the average price per hectare was $1690. The lowest average was in the Kherson region, at only $830. However, the process was non-transparent – these averages only take into account 54 per cent of sales.

The liberal publication Liga promises that the price will rise in the future. It also includes calculations given by an EU-sponsored think tank ‘Land Transparency’ in cooperation with a World Bank official, according to which any restrictions on the concentration of land ownership or on foreign control over land will lead to a slower rate of Ukrainian GDP growth and a slower rate of growth in land prices. In the most unregulated scenario, Ukraine would supposedly gain $10 billion. Tymofiy Mylovanov, a notoriously neoliberal advisor to the president’s office, promised that land privatization would increase GDP by 1.5 per cent per year.

The same Liga publication records that three months later (January 2022), the average price of land had fallen to $1500 per hectare. While the article does not mention this, the threat of war likely played a role here. Nevertheless, in the midst of the anticipation of war (December 2021), the economy minister promised that the price of Ukrainian land would rise to $2200 by 2-3 years. Faith in the market knows no bounds.

Agricultural trade with the EU

Western nations and domestic agricultural latifundists ceaselessly pushed on the Ukrainian government government to lift the moratorium on buying and selling agricultural land. This move gave power to big agroholdings. These companies, which decide on what to invest in based on the price trends in top export markets like that of the EU, set about deepening Ukraine’s neocolonial trade relation with the EU. Where the EU sells Ukrainian agrobusiness means of production and processed food goods, Ukraine sells back cheap agricultural raw materials.

Illusions and reality of ‘eurointegration’

Ukraine’s modern history has been transformed by the question of signing a free-trade agreement (FTA) with the EU. This was generally misrepresented by its supporters as being equal to joining the EU.

All kinds of promises were made about the magical results of the FTA. It was said byv supporters such as Maidan Prime Minister Yatsenyuk (of Victoria Nuland phone call fame) to bring instant economic prosperity. They would often refer to the pension and wage levels of Germany as an obvious disproval of all the ‘Eurointegration’ doubters, who reasonably pointed to the deindustrializing effects of giving EU capitalists access to the Ukrainian market, and the inherently unequal terms of the agreement. Yatsenyuk and the other ‘principled supporters of Eurointegration’ (generally urban journalists on western grant money who had never stepped foot in a factory) always loved talking about how ‘integration with the EU will give Ukrainian exporters access to the biggest market on earth’.

The problem is that this was always explicitly contradicted by the actual FTA, which entered into practice in 2016. It involves harsh quotas for Ukraine’s top exports. This means that only a comparatively small amount of Ukraine’s exports can actually reach the EU without paying tariffs, while the much stronger (and highly state-supported) European producers are free to invade the Ukrainian market.

2019 was post-Maidan Ukraine’s best trade year[2], but exports to the EU only increased by 3 per cent. During the 2020 Covid pandemic, while the EU tightened access to its markets, it forbade Ukraine from taking any steps to protect its markets. As a result, exports to the EU tumbled by 13.2 per cent.

Ukraine’s total exports in 2019 were only $63.5 billion according to the World Bank – in 2012, they were $86.5 billion. Industrial exports to the EU even declined by 2.3 per cent. While Ukraine’s total vegetable exports increased from $6.6 billion USD to $17.6 billion USD in 2010-2020, its machine and transport equipment exports decreased from $9.1 billion USD to $5.4 billion. Exports to Europe accounted for only $3 billion USD of the increase in vegetable exports – China and other countries of the ‘barbaric East’, so reviled in the hegemonic post-maidan Ukrainian discourse, are responsible for much of its export growth. The sluggish growth of exports to the EU has not been enough to compensate for the loss of the Russian market for industrial goods, and for a general decline in exports due to FTA-induced deindustrialization.

Programmed inequality of the EU Free Trade Agreement

In 2021, the five-year period approached when Ukraine was entitled to renegotiate the EU FTA. Something approaching negotiations on the topic took place. To which the EU answered, as usual, that there could be no such relaxations in trade relations until Ukraine tried harder to implement reforms demanded by the EU. The reforms demanded by the EU, such as the ‘struggle against corruption’, invariably involve removing support for Ukrainian industry.

The EU representative declared that Ukraine would receive neither full access to the EU market of state purchases, nor a relaxation in the quota regime. Things only changed in 2022, when Ukraine’s industry became largely destroyed by war – then the EU declared that Ukraine could have tariff free access to EU markets for a limited period.

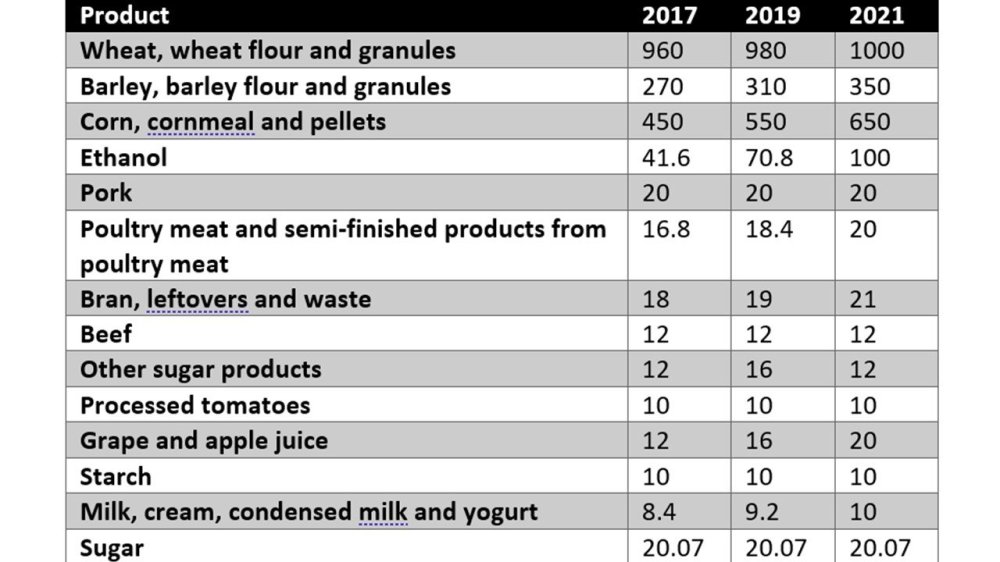

What are these tariff quotas? The 2016 FTA gave tariff-free access to 36 (+4 extra) groups of Ukrainian exports. Only agricultural exports received this privilege. Occasional noise about tariff-free access for Ukrainian industrial goods never came to anything until 2022. The FTA involved a small increase in some of these quotas over time. The following table shows the change over time of these tariff-free quotas for only those exports whose yearly volume exceeded 10,000 tons.

Size of tariff quotas for main Ukrainian exports to the EU, 2017-2021 (thousands of tons).

These quotas are highly restrictive. In 2021, Ukraine exported to the entire world 42 times more wheat than allowed the EU quotas, and 21 times more than the EU quotas. The EU imported 18.5 times more corn from Ukraine than what the quotas allowed. This is despite the fact that Ukraine is indeed a crucial source of grains for the EU – the second biggest source after France, accounting for 14 per cent of total EU imports of corn, wheat and other grains.

While Ukraine exported 81 000 tons of honey in 2020, it is only allowed six thousand tons by the 2021 quotas. The milk quotas allowed by the FTA were only 0.007 per cent of total Ukrainian production, while Ukraine produced 66 times more meat than allowed by the quotas in 2015. In 2019, while Ukraine exported 414 000 tons of chicken meat, it was only allowed 19 200 tons of customs-free exports to the EU. As Ukrainian chicken magnate Yury Kosyuk said:

“There has been no opening of the [EU] market. You know, there is a mechanism in the wheel called a spoke nipple. It allows something to pass in one direction, but not to pass in the other direction. This is approximately the situation we now have with the European markets. Europe talks about a free trade zone with Ukraine, and at the same time a bunch of exceptions and restrictions have been put in place for the export of Ukrainian goods… while we produced 1.2 million tons of chicken meat in 2016, anything over the 16-000-ton quota is charged with a tariff rate of more than 1000 euros a ton… Ukraine has been tricked by this ‘free trade agreement’’“

The story with restrictive quotas can be continued extensively. Ukraine also regularly exceeds quotas for juice, tomatoes, and cereals.

Even these meagre benefits are only given to primitive agricultural goods. Ukraine has had no luck in receiving any such privileges for its industrial goods. It is worth mentioning some impressive figures brought up by a 2020 report by the ministry of economy, as part of its ill-fated drive to implement state support to domestic industry (subsequently halted by the EU):

“the production of motor vehicles in 2019 amounted to only 31.0 per cent of the level of 2012, the products of the railcar industry – 29.7 per cent, the production of machine tools – 68.2 per cent, metallurgical products – 70.8 per cent, agricultural engineering products – 68.4 per cent”…

“Between 2013-2019, exports of aerospace products decreased by 4.8 times (from $1.86 to $0.38 billion), production of railcar products – by 7.5 times (from $4.1 to $0.5 billion), production in the metallurgical sector – by 1.7 times (from 17.6 to 10.3 billion US dollars), chemical products – by 2.1 times (from 4 to 1.9 billion dollars)”

On the other hand, after a three-year transition period, Ukraine was obliged by the FTA to remove import tariffs on a range of EU imports in 2019. In 2016, the Ukrainian government had agreed to totally remove or reduce import tariffs for most EU imports within three to 10 years. The EU only exceeded one export quota to Ukraine in 2017 – chicken meat. It only used 5 per cent of its pork export quota, and 0.5 per cent of its sugar quota.

Other forms of EU agricultural protectionism

Besides the quotas, the EU FTA also obliges Ukraine and the EU to ‘refrain from any state subsidies’ for exports. In conditions where Ukrainian agriculture is far weaker than EU, while the EU hypocritically gives immense subsidies to its farmers, this has naturally led to domination by EU imports and decline of Ukrainian production.

Another form of hidden protectionism is the EU’s stringent restrictions on food imports. Due to various ecological and quality controls, many Ukrainian exports cannot enter the EU. This is one of the main reasons, along with the tiny quotas, that Ukrainian agricultural exports have been forced to reorient towards Asia and Africa.

Neo-colonial trade relations

Along with a huge trade deficit, the EU sells Ukraine processed goods, while Ukraine exports cheap raw materials. A good example of the primitive nature of Ukraine’s agricultural sector is Ukraine’s tractor trade. While it exported $4.7 million worth of tractors in 2020, it imported $456 million. 59 per cent of those tractors were imported from the EU, and another 12 per cent were from the US and UK. The rich first world imports cheap food goods from Ukraine, extracting large tariff revenues in the process, and sells Ukraine the industrial machinery needed for this agriculture.

For instance, Ukraine’s main exports to the EU in 2021 were iron and steel (20.8 per cent of total exports), ores, stag and ash (12.5 per cent), animal and vegetable fats and oils (8.5 per cent) – mainly sunflower seed oil, electrical machinery (7.8 per cent) and cereals (7.3 per cent). ‘Electrical machinery’ is actually mostly just the manual screwing together of wires in small sweatshops as part of European car production chains. The EU’s main exports to Ukraine were machinery (14.8 per cent of all exports), transport equipment and vehicles (10.2 per cent), mineral fuels (9.4 per cent), electrical machinery (9.3 per cent), and pharmaceutical products (5.9 per cent).

European exporters have actively entered and mastered the Ukrainian market. In 2019, the Ukrainian destination set a record for growth in European food exports. Ukraine took third place in the ranking of consumers of agricultural products from the European Union. In the first half of 2019, the EU increased agricultural exports by 15 per cent compared to 2018, reaching 2.26 billion euros. In 2020, Ukraine imported 1000 times more butter from the EU than it exported. In 2021, Ukraine had an overall trade deficit of over 4 billion euros with the EU.

Domestic producers are losing competition and shelf space to European manufacturers. Unlike Ukraine, producers in Europe are protected by high duties, tight quotas and receive huge subsidies from the general budget of the European Union. Ukrainian economic journalist Roman Gubrienko argues in his articles on the topic that the rapid advance of imported food products leads not only to the capture of the market and the displacement of Ukrainian agribusiness, but also gradually destroys the basis of domestic food production – the topic of the next article.

Notes

[1] Australia being a notable exception.

[2] 2021 had higher export figures in dollars, but this was due to post-covid global price rises on raw materials exported by Ukraine

Part II: Crippling agricultural capacity: The so-called Western ‘help’ for Ukraine

Grain being harvested in Odessa, Ukraine. Image credit: CGTN.

In 2016, US ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt stated that “Ukraine is already one of the largest producers of agricultural commodities, but it must become an agricultural superpower”.

The description of Ukraine as a ‘guarantor of global food security’ has become a classic of publications concerning Ukraine in the Euro-Atlantic press. This article will examine the reality behind the boasts of the US government regarding Ukraine’s liberalized agriculture. How effective and sustainable is Ukraine’s liberalized agriculture at feeding its citizens?

Primitivization of Ukrainian agriculture

In 2020, Ukraine’s Deputy PM for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration delivered the stock usual euro-optimist litany, which hasn’t changed an iota since 2013-era Yatsenyuk promising the German lifestyle from signing the EU free trade agreement:

“The association agreement and the free trade area with the EU have become the engine for the development of the Ukrainian economy – because it opened the way to the largest market on the continent”

This market, however, has only been interested in a small list of extremely primitive Ukrainian goods. UkraineInvest, the government agency which advertises the country for foreign investment, promotes Ukraine as ‘the land of agri opportunities…. with cheap labour … and cheap land rent’. In 2019, agricultural and food exports rose the most of all economic sectors compared to 2018 – by 19 per cent. But eeprocessed agricultural exports only rose by 5 per cent, thanks to sunflower oil. In the first half of 2020, when the EU closed off its market to Ukraine but did not allow Ukraine to do the same during Covid, trade turnover between the two fell by 5.1 per cent. In this same period, over half of Ukraine’s exports to the EU were composed of cereals, sunflower oil, processed food waste, and oil seeds.

9.4 per cent of all imports in 2019 were agricultural goods and food products, $5.7 billion worth of production. 46 per cent of all agricultural imports were finished food products, with the proportion of such goods imported from abroad growing by the year.

Ukrainian economic journalist Roman Gubrienko summarizes the situation whereby Ukraine’s economy is highly dependent on a very primitive agricultural sector:

Almost 50 per cent of Ukraine’s state revenues are dependent on the export of products and services to foreign markets. At the same time, about 40 per cent of foreign exchange export earnings come from products of the agro-industrial complex. According to the State Fiscal Service, in 2019 the export of Ukrainian agricultural products grew by 19 per cent, amounting to a record $22.2 billion. Of the entire array of agricultural products, only 202.9 million dollars worth of ready-made food products were exported.

Ukraine imported 30 per cent more processed vegetable goods than it exported in 2021. It imported six times more finished meat and fish products than it exported in 2021. It only imported 3.5 times more finished meat and fish products than it exported in 2012, so the situation has certainly worsened. The only good classified as ‘finished food product’ which it succeeded in achieving a trade surplus was sugar, hardly a technologically complex product, and one where imports are still 70 per cent the size of exports and growing.

Of the 90-95 million tons of agricultural crops harvested on average in recent years, 60 million is instantly exported and only the remaining 30-35 million is subjected to minimal domestic reprocessing. Of 70 million tons of grain goods harvested, only about 20 million is domestically processed. The only sector where significant amounts – still only slightly over half – of production is domestically processed is the sunflower oil sector.

It is only fairly primitive forms of agriculture that have consistently increased production in Ukraine since Euromaidan. Animal and vegetable oils (read: sunflower oil) exports rocketed up from $4.1 billion USD in 2012 to $7.3 billion in 2021. Grain exports rose from $7 billion to $12 billion. The following graph shows which agricultural products it exported more than it imported and which agricultural products it imported more than it exported in 2021:

As can be seen, Ukraine exports unprocessed agricultural goods, and imports food products and processed agricultural goods.

Decline in Ukrainian livestock production and quality

In our last article, we saw how big agrobusiness has risen at the cost of smaller farmers. But these small-scale farmers are crucial for Ukraine’s food supply. While only using 12 per cent of Ukraine’s total farmland, they produce over 50 per cent of the country’s agricultural output – 98 per cent of potatoes, 89 per cent of vegetables, 78 per cent of milk, and 74 per cent of beef.

In January 2020, the volume of Ukraine’s gross agricultural production declined by 0.7 per cent compared to January 2019. In January 2019, it only increased by 3 per cent. But the situation is worse when you look at individual sectors of agricultural food production.

Livestock

In 2018, when confronted with evidence of huge subsidies for his and others’ agroholdings, Poroshenko ally Yurshinin responded that ‘the government cares deeply for the state of livestock farming in Ukraine, that is why we received these funds’. Whatever ‘care’ the government has for livestock farming, it has not amounted to much.

In 2018 and 2019, the number of cows, pigs, sheep, and goats per capita declined. Only the amount of birds farmed increased, due to their popularity on export markets. The following graph from Roman Gubrienko shows the change in Ukraine’s food production for 2019. The important part of this graph is the orange – this represent the number of these livestock per capita, as a per cent of the 2018 figure. As can be seen, there was a large decline in livestock for all non-bird sectors from 2018-2019.

This is all because of the economic liberalization of Ukraine’s agricultural market. It takes less time to grow birds for export than it does for other livestock, so agroholdings invest in birds. The production of pigs, cows, and sheep has negative profit rates in Ukraine – from -7 per cent to -25 per cent. As we mentioned in our previous article, another factor are huge subsidies for big poultry agroholdings like that belonging to Yuri Kosyuk, a good friend of Poroshenko and the US State Department.

From April 2019-April 2020, the number of pigs in Ukraine declined by 6 per cent, a loss of 400 thousand pigs. In the first 4 months of 2020, 3500 tons of pigs were imported – 2.3 times less than the same period a year ago, a telling indicator of the decline in Ukrainian consumption as a result of the covid quarantine. Only 900 000 tons of pigs were exported in the same period, 75 per cent of which went to the UAE as part of special agricultural agreements signed with Ukraine.

The situation was no better in 2020-21. In this period, there were declines of 5-6 per cent in all forms of livestock (including poultry) apart from pigs – here, the growth of large agroholdings specializing in pigs cancelled out the decline in small scale pig farming. Nevertheless, pig numbers only increased by 3.7 per cent. However, the amount of pigs in 2021 was still lower than the amount in 2019, meaning that the brief increase did not compensate the losses of the catastrophic Covid year in 2020.

Despite previous successful years, poultry exports declined in 2020 because of the difficulty of exporting chicken meat and eggs to the EU due to the quarantine. The EU increased its support to domestic farmers, while also forbidding Ukraine from doing the same for its own businesses. As Gubrienko writes, big Ukrainian agroholdings have no interest in supplying the small domestic market of low wage-Ukrainians, meaning that any fluctuations on export markets have negative effects on Ukrainian agriculture.

Dairy

2020 was the first year that Ukraine became a net importer of dairy products, with exports in the first quarter decreasing by 9.3 per cent and imports increasing by 167 per cent. As a result of the decline in the cow industry, where the number of this form of livestock declines by 5-7 per cent every year, the milk industry, despite its profitability, has also suffered. This also results in a decline of Ukraine’s precious food processing industry, like that creating cheese or kefir (a fermented milk drink popular among the eastern Slavs). In 2019, there was a 25 per cent decline in milk per capita that went to reprocessing facilities compared to 2018, or a 9 per cent gross decrease. The amount of high quality milk purchased by processing facilities declined by 53 per cent per capita.

Ukraine’s milk industry began seriously declining in 2018, when exports fell by 40 per cent compared to the previous year. According to state statistics, after the first 3 months of 2020, Ukraine was already a net-importer of milk products. By the first half of 2020, Ukraine’s milk exports had declined by 9 per cent, while imports increased by 168 per cent as compared to the same period of the previous year. According to the association of milk productions, after the first 10 months of 2020 milk exports had declined by 20 per cent compared to the same period in the previous year. According to state statistics, 2020 was a record year for Ukrainian cheese imports, more than doubling the previous years’ figure. Milk and cream imports, meanwhile, increased by 310 per cent.

The number of cows decreased by 6.35 per cent in 2019, as compared to 2018. According to the national scientific center ‘Institute of Agrarian Economics’, Ukraine’s milk production will fall by 12.3 per cent by 2030, with family farming production falling by 31.1 per cent. Gubrienko grimly jokes that cows will soon have to be placed on the red list of endangered animals in Ukraine.

In the first quarter of 2021, the amount of Ukrainian milk heading towards processing facilities in Ukraine declined by 12.3 per cent. The same figure declined by 9.1 per cent and 7.6 per cent in 2019 and 2020. In 2020, only a third of the milk that went to processing facilities in Ukraine came from Ukraine.

Decline in food quality

Not only has the milk industry declined, but so has the quality of milk sold. The state department of consumer service stated that milk products are the food group most commonly sold with fake ingredients in Ukraine. They are constantly forced to fine milk product distributors tens of millions of hryvnia for selling milk products which do not contain real milk. Often, butter and cheese is secretly made with trans unsaturated fat, emulsifiers and palm oil.

One reason for this, according to Gubrienko, is the weakness or lack of state bodies to rigorously monitor food quality production. In the deregulated environment, businesses do whatever it takes to get the highest profits – the state anti-monopoly committee said that one dairy company earned 100 per cent profits by using illegal non-milk ingredients.

Gubrienko argues that this is also due to the decreasing amount of domestic cow numbers and milk production – as a result, for milk-intensive products like butter, producers are forced to supplement real milk with less healthy products. The amount of dairy production and exports far exceeds the amount of dairy products that could be produced in Ukraine given its annual milk production. He calculates that from 25-50 per cent of Ukraine’s dairy products involved falsified ingredients.

Food inflation and hunger

Despite its enviable status as a guarantor of global food security, according to Ukrainian state statistics food prices rose by 10.9 per cent from January-October 2021, as compared to the same period in 2020. Egg prices increased by 54 per cent, sugar by 69 per cent, bread by 15 per cent, and sunflower oil by 61 per cent. This is despite Ukraine’s famed status as the world’s top sunflower oil exporter.

While agricultural goods as per cent of total exports rose from 39 per cent in 2018 to 44 per cent in 2019, we already know that this is not thanks to increases in livestock production. The top Ukrainian agricultural goods exported are wheat, corn, and sunflower oil, goods for which Ukraine is among the global export leaders.

Liberal experiments in price deregulation

The former Canadian ambassador to Ukraine Roman Waschuk famously called post-maidan Ukraine a ‘laboratory for ideal-world experimentation’. One such experiment was in the field of price regulation – in 2016, state regulation of food prices was temporarily cancelled, and in 2017 this regime was made permanent. The liberal, pro-west prime minister of the time, Volodymyr Groisman, explained it by saying that state regulation is in itself ineffective and had not stopped price increases anyway.

Borscht catastrophe

In 2018, the ‘borscht-basket’ – a measure of the price of vegetable goods most commonly consumed by average Ukrainians in the national soup dish – rose in price by five times. In January-October 2019, the amount of imported cabbage, carrots and capsicum rose by 20-30 per cent compared to the same period in 2018. Imports of tomatoes increased by 15 per cent and imports of cucumbers by 38 per cent. Imports of onions increased by 26 times. The worst situation was in potato production – here, Ukraine imported 700 times more in June-October 2019 than it did for the same period in 2018. They were mostly imported from Belarus and Russia. Gubrienko ties the fall in potato production with Ukraine’s Covid quarantine restrictions on farmers markets, which led to protests by small farmers in the Kherson region.

Summarizing state statistics, the analytics company EastFruit writes this about inflationary trends in the ‘borscht basket’:

“Wholesale prices for carrots are twice as high as last year, prices for onions are two and a half times higher, prices for white cabbage are three times higher, and prices for table beet are also three times higher. That is, the average prices for the borscht vegetables have increased by 2.6 times compared to the beginning of December 2020″.

In Gubrienko’s words, ‘judging by the dynamics of prices for borscht products, the sacred Ukrainian dish will move away from being a traditional national cuisine towards becoming an elite gastronomic one.’ This is the uncomfortable reality behind the patriotic hysteria of the government, which sponsored a TV series ‘the history and traditions of preparing borscht’, including online battles on the best borscht recipes. The official Ukrainian Twitter account often goes on online offensives to make sure borscht is considered a uniquely Ukrainian, not Russian food, taking the matter all the way to UNESCO. This is despite the fact that most of its ingredients are imported, even coming from ‘enemy nations’ such as Belarus and Russia.

Gubrienko believes that the major factor behind the rising cost of borscht is Ukraine’s dependence on importing all the ingredients. Apart from the usual EU suspects, Ukraine imports pork from the USA and Norway, and onions from Uzbekistan and Mexico. Importing these products from so far away itself adds to the price. In addition, its top supplier of potatoes is Belarus, with which Ukraine constantly strives to conflict with as a way of signaling its worth to the US as ‘the frontier of Western civilization’.

In 2020, even tiny Albania was the absolute leader in supplying Ukraine with cabbage. Albania exported $425 million dollars worth of cabbage to Ukraine, covering 90 per cent of Ukraine’s import needs. Ukraine, meanwhile, only exported $116 million worth of this stable vegetable.

Ukraine imported 1377 times more potatoes than it exported in 2020. ‘Authoritarian Belarus’ was the leader – not coincidentally, it has a highly developed system of state assistance to small and medium farmers.

Ukraine’s potato problems also shed light on its exploitative relation with the EU. In May 2020, it emerged that Dutch potatoes which were only used to make French fries (that couldn’t be sold at the time due to covid lockdowns) were shipped off to Ukraine to be consumed as normal potatoes, which is illegal in the EU. They sold for the same price as Ukrainian potatoes in Ukraine. If not for this, these potatoes would have been destroyed.

While Ukraine at least exports decent amounts of carrots, it still imports 3 times more. And worse, it mainly imports them from high-wage EU countries, meaning that while EU consumers get cheap Ukrainian carrots, poor Ukrainian consumers need to pay high EU prices for basic food goods. The situation with beetroot, the main ingredient of borscht, is very bad – Ukraine exports none, and imports $40 million dollars-worth, all from Italy – a country whose farms are filled with Ukrainian migrant workers fleeing from unemployment. Ukraine has fertile soils and talented workers, but it buys agricultural goods from abroad.

The situation is also bad in buckwheat production, a staple food in Ukraine, especially for the poor. In the first half of 2019, Ukraine imported twice as much as it exported, with the amount of sown land dedicated to this crop declining by 10 per cent compared to 2018. While it exports huge amounts of corn and wheat, Ukraine’s imports of all cereals and grains increased by 2.4 times in 2018.

Collapse of the pig front

Salo – cured pig lard – is another contender for Ukrainian national dish. Unfortunately, 2018 was a record year for pork and salo imports, increasing by 520 per cent compared to the previous year. The beneficiaries of this increased pork import demand were, as usual, Ukraine’s ‘european allies’ – Poland, Germany, and the Netherlands. Ukraine’s 2018 exports of pork also declined by 36 per cent. The situation did not improve in 2019, with pork imports in the first half of the year increasing by another 5 per cent. Ukraine only exported 32 000 tons of salo, importing 30 000 tons.

Caption: A helpful infographic from Gubrienko. It shows the per cent increase in imports of various food goods in the first half of 2019, as compared to the same period in the previous year. The top three foods don’t show per cent, but by how many times imports have increased.

The salo situation got even worse in 2021. In the first ten10 months of that year, Ukraine imported four times more salo than it produced. Gubrienko describes two main processes leading to the decline of this national cuisine product. Over the past 30 years since the end of the USSR there has been a constant decline in the number of swine. The scale of the decline is immense – in 1990, there were 20 million pigs in Ukraine, and by 2021 – 5.9 million. In the privatizing chaos of the 1990s alone, pig numbers declined by 60 per cent, to 8.4 million. The second stage was from 2000-2011, when the number of pigs declined due to urbanization, migration, and general depopulation of the countryside areas, resulting in a decrease in domestic farming of pigs. The third stage was from 2011-2016, when agroholdings began developing more rapidly. This was a period of slower decline, with pig stocks decreasing by 500 thousand. The final stage was from 2016-2021, following the victory of the Euromaidan coup and Ukraine’s free trade agreement with the EU. With all economic regulation gone and full power in the hands of big agrobusiness, the number of pigs declined by over a million in only 5 years.

Gubrienko goes on to show that due to the critically low amount of domestic pigs, the years when Ukraine has processed the most salo are the same years that Ukraine’s live pig imports soared. In other words, Ukrainian salo production has become dependent on imports. He also discusses how Ukrainian domestic salo price levels have become dependent on import levels. Considering Ukraine’s debt and currency reserves problems, this is a quite dangerous situation. It is noteworthy that prior to 2014, Ukraine imported almost five times more pigs and salo per year than after. It is possible, though Gubrienko does not mention this, that this is due to the import restrictions placed on Ukraine following the 2014 adoption of harsh IMF austerity measures, the collapse of exports, the decline of domestic purchasing power, and the devaluation of the currency.

One of the main causes for this pig apocalypse is what Gubriienko calls the ‘blitskrieg offensive’ of western producers into Ukraine’s swine market. Before 2009, 95 per cent of Ukraine’s swine and salo imports were from south America. But by 2015, 70 per cent of all Ukraine’s pig product imports, and 100 per cent of all salo imports were from the EU. Poland, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada were the main sources – another way that the west has benefited from Ukraine’s ‘civilizational choice in favor of the Europe’, a choice that has been much more beneficial for one side than the other. Out of the $20 million worth of pork products imported by Ukraine in 2020, $6.5 million was from Canada – Canada imported none of these products from Ukraine, showing how much exactly of a mutually beneficially relationship they enjoy. But Ukraine’s weak domestic agriculture means that other forms of national betrayal are also possible – Ukraine’s main source for salo in the second half of 2021 was Russia.

Causes of food inflation

In August 2021, food prices in Ukraine continued rising. Gubrienko points out that this is contrary to global trends, where food prices declined 1.2 per cent in comparison to July. He wonders why global price trends have not pushed down Ukrainian food prices, since the government always referred to global price trends in justifying food price inflation in the past. Gubrienko calls this the ‘paradox of the Ukrainian agricultural superpower’. Prices for pork, eggs, milk and chicken meat rose by two to five per cent in just the second week of August. This is all despite the fact that prices for agricultural goods should fall at this time of year as the harvest comes through. The food price index as a whole rose by 8.6 per cent from January-August 2021.

Why have prices kept rising on Ukraine’s domestic food market? One crucial role is the fall in domestic production, replaced by goods that are often more expensive since they must be imported from countries as distant as Canada.

An expert interviewed by Gubrienko argues that the uncertain political situation surrounding the trade war between Ukraine and Belarus, began by Ukraine in its indignation at Belarus’s ‘authoritarian human rights abuses’, was likely to blame for producers increasing food prices in 2021 despite global trends.

Importer cartels are also a factor. It is a much-derided fact that sunflower oil is two times more expensive in Ukrainian supermarkets than in Poland. This means that Ukrainians, whose wages are two to three times lower than Polish wages and many times lower than EU wages, end up paying more than EU citizens do for them. Ukrainian news portal UNN writes that the fact that the anti-monopoly committee has been investigating this problem for five years, with no verdict, is clearly politically motivated. They link this to the wealth of Berevzsky, the owner of Ukraine’s biggest agroholding ‘Kernel’, and one of Ukraine’s 20 richest men.

The problem of importer cartels is not limited to sunflower oil. The Union of Ukrainian Businessmen sent a letter to the Ukrainian anti-monopoly committee to curb the rise in sugar prices, which rose 170-190 per cent over global sugar prices over the past year. They blame this on price cartels among sugar producers and importers and also note the damage on production caused by price rises on this important product.

Despite exporting slightly more than it imports, as for most agricultural products import substitution has also played a role in sugar price increases. Exports fell by 31 per cent in 2019 and 2 per cent in 2021, while imports rose by 5 per cent in 2019 and by a stunning 132 per cent in 2021. By 2021, Ukraine was exporting $24 million worth of sugar and importing $17 million.

Another factor is energy inflation. This, in turn, is largely due to Ukraine’s bad relations with Russia, an energy war exploited by the USA in its aim to get Europe buying American gas and trade less with Russia. As a result, Ukraine in 2021 was among the top 5 countries when it came to energy prices.

Global food security but domestic hunger

While Ukraine tops the charts in export of primitive agricultural raw materials like sunflower oil and corn, it received the 63rd spot out of 113 countries rated by the global index of food security. Gubrienko compares Ukraine with other food insecure nations such as Somalia. Such countries have no state interference in the economy, meaning that agriculture is grown for export to the detriment of domestic consumers. Big agroholdings don’t have any interest in satisfying Ukraine’s tiny internal market – in 2021, 85 per cent of Ukrainians earned less than $300 a month.

UNICEF annual hunger reports found that 20 per cent (almost 9 million people) of Ukrainians in 2018-20 suffered from ‘moderate to severe food insecurity’, and 22.7 per cent (10 million people) in 2019-21– for comparison, the average score in Europe was 8 per cent. This places Ukraine at around the same level as Brazil (in the 2014-16 period, Ukraine’s situation was even worse than Brazil’s), where 23.5 per cent of the population suffered from moderate and severe food insecurity in 2018-20. According to the global hunger index, the amount of Ukrainians suffering from hunger rose stayed at 7.2 per cent in 2007 and 2014, rising to 7.5 per cent in 2022. This is a higher level than that in Iran, Uzbekistan and Mongolia.

The fall in incomes and employment resulting from Euromaidan was reflected by a fall in real consumption. According to official Ukrainian statistics, in 2013 54 per cent of Ukrainian earned less than $280 a month. In 2020, 85 per cent of Ukrainians earned less than $291 a month. Average household meat consumption only returned to its 2013 level of 5.1 kg in 2019 – it had fallen as low as 4.6 kg in 2015.

Black soil, dead soil: ecological degradation

Here is the final sad irony. Not only can the guarantor of global food security not feed its own citizens. The narrow, export-based ‘corn and sunflower republic’ is destroying its famous ‘ultrafertile black soil’.

One ominous sign has been the decline in the area of sown agricultural land sown. The ten year peak was reached in 2013, with 28 million hectares sown. During the 2008-09 and 2014-15 crises, this figure declined to 26.8 million hectares. In 2020, around 24 million hectares were predicted to be sown.

Nevertheless, exports of primitive agricultural raw materials have been booming – 2019 was a record year for exports of grains and legumes. While agriculture for domestic consumers is suffering, agriculture for export has never done so well. 2020 saw farmers increasing the share of sown land dedicated to sunflower oil, corn, and soy, while decreasing the amount dedicated to wheat, vegetables, potatoes and sugar beet. This is all due to price trends on the global agricultural market, and also contributes to domestic price inflation for these food goods.

The quality of Ukrainian agricultural land is not a matter of concern for the government. They limit themselves to declarations on the fantastic productivity of Ukraine’s black soil, which can only be unlocked through privatization. The last state program on the preservation of soil quality was created in 2008-9. Its ambitious goals were never realized. The State Cadastral Service (Gosgeokadastr) has never been able to collect a full base of information on all Ukrainian agricultural land. The problem of soil quality is no longer brought up by the Ukrainian government.

Timofey Milovanov, the economically libertarian minister of economic development, declared in 2019 his desire to liquidate Gosgeokadastr. A law project to that end was submitted, where Gosgeokadastr would be ‘decentralized’ in the course of the liberalization of agriculture, with control given to ‘local communities’. Though this project was not implemented, Gosgeokadastr remains quite neglected and ideas to remove it are popular among the ruling elite.

Gosgeokadastrv conducted 199 inspections of agricultural land from December 2019 to January 2020. It found 111 violations of agricultural legislation. Thus, even this superficial investigation revealed that Ukrainian agricultural land is being harshly mistreated by capitalist agriculture.

According to a 2021 study by the NGO Eco-Action and the Ukrainian Institute of Geology, the concentration of Ukrainian land by agroholdings has had parlous effects on Ukrainian soil quality. The rise of agroholdings has meant that 40 per cent of Ukraine’s arable land is intensively farmed with monocultures – corn, sunflower, rapeseed and soy. The share sown with these monocultures rose by 2.7 per cent from 2017-2020, and by 6.9 per cent in the black-soil central and western regions of Ukraine.

The study argues that all this land is hence at risk of becoming infertile – nearly half of Ukraine’s arable resources. In 2020, about 83 per cent of Ukraine’s agricultural land was sown with grains – ‘absolutely barbaric, no culture of arable farming’, in the words of a Ukrainian agricultural expert.

The last detailed data on the condition of Ukrainian agricultural soil comes from the state institute for the preservation of Ukrainian soil (SIPUS), in its 2018 report on conditions in 2011-2015. This is what it had to say:

Long-term intensification and excessive plowing have led to a threatening state of the soil in Ukraine. The main reasons for the decline in agronomically important soil properties are insufficient application of organic and mineral fertilizers, water and wind erosion, and over-consolidation by powerful heavy machinery. On the territory of Ukraine, 57.5 per cent of agricultural soil is subject to erosion, and these tendencies are continuing

The report also blamed excessive use of nitrogen fertilizers for increasing harvest sizes at the cost of decreasing long-term soil fertility. The report finds Ukraine’s agricultural liberalization to blame for many problems. For instance, the lack of state funds dedicated to analyzing the agrochemical condition of Ukrainian soil. Or the lack of state regulation, which allows agricultural producers to do with their soil whatever they wish.

In Ukraine, it is popular to compare Ukraine with the EU, but generally with the aim of convincing the reader to agree to all the demands made by Ukraine’s ‘western partners’. Gubrienko also compares the EU to Ukraine. He describes how the SIPUS report favorably compared Germany’s agricultural system to Ukraine’s. In Germany, there is a complex system of soil regulation. Agricultural producers must plant certain crops in line with the recommendations of the soil quality advisors. This contrasts with Ukraine, where crop choices are made according to the whims of the global market, with no regard for soil quality. In addition, in Germany the size of agricultural land owned by each company is limited – hence, the average amount of agricultural land owned by farmers is 20 hectares. Monoculture farmers are limited to owning 5-6 hectares of land. 400-500 hectares is considered large by German standards. In Ukraine, meanwhile, big agroholdings own 300-500 thousand hectares of land.

Ukrainian agrochemical scientist Vadym Ivanin said in an interview that while in western European countries no more than 50 per cent of agricultural land is cultivated, and in the US 25 per cent, while the rest is used for grazing and other uses. This allows adequate recovery of soils. In Ukraine, however, 90 per cent is cultivated, and there is hardly any grazing land. Ivanin also recommends increasing the amount of forested land by 12 times to prevent erosion – apart from the Carpathian region, only 15 per cent of Ukraine’s steppe area is covered by forests. In the EU, no countries have less than 26 per cent.

It is worth mentioning here that Ukraine’s Carpathian forests have been dramatically exploited in recent years by European logging companies. An attempt to implement an export ban in 2015 was ruled illegitimate by the EU, due to Ukraine’s responsibilities in its FTA with the EU. Ukraine serves as the source for cheap timber used by ‘civilized’ European brands like Ikea. An apt illustration of general trends.

Part three of this series will be where Canada’s role is discussed.

Peter Korotaev writes on political movements, class relations, and economic policy in Ukraine. You can follow his work on his substack, “Events in Ukraine“.