The Wave (1889), Ivan Aivazovsky

The Wave (1889), Ivan Aivazovsky

Once again, the assertion put forward in the essay is factually correct. “The Met continually researches and examines objects in its collection in order to determine the most appropriate and accurate way to catalogue and present them,” a Met spokesperson said, commenting on the reclassification. “The cataloguing of these works has been updated following research conducted in collaboration with scholars in the field.”

The “collaboration” the Met speaks of came in the form of online pressure from someone the Met described as a Ukrainian art historian, Oksana Semenik, whose Twitter account, Ukrainian Art History (@ukr_arthistory) ran a concerted campaign criticizing the Met for incorrectly labelling the works of Arkhip Kuindzhi as Russian. “All his famous landscapes were about Ukraine, Dnipro, and steppes,” Semenik tweeted. “But also about Ukrainian people.”

But, as the Ambassador’s essay points out, “This does not withstand any criticism at least because the artists considered themselves Russians. Just in case: ethnically, Ilya Repin was Russian, Ivan Aivazovsky was Armenian and Arkhip Kuindzhi was Greek. All three were born in the Russian Empire – when Ukrainian statehood did not exist.”

Kuindzhi was a landscape painter from the Russian Empire of Pontic Greek. When he was born, in 1841, the city of Mariupol was one of the subdivisions of the Yekaterinoslav Governorate of the Russian Empire. The landscapes he painted were, at the time they were produced, depicting Russian scenes, and Russian people. Kuindzhi, by any account, was a Russian artist.

While Ivan Aivazovsky may have been ethnically Armenian, he and all of Russia considered (and considers) him to be an iconic Romantic painter who is considered one of the greatest masters of marine art of all time. Indeed, several of Aivazovsky’s works hang in Ambassador Antonov’s residence in Washington, DC.

Prior to the reclassification, the Met described Aivazovsky as such: “The Russian Romantic artist Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817–1900) was widely renowned for his paintings of sea battles, shipwrecks, and storms at sea. Born into an Armenian family in the Crimean port city of Feodosia, Aivazovsky was enormously prolific—he claimed to have created some six thousand paintings during his lifetime. He was a favorite of Czar Nicholas I and was appointed official artist of the Russian imperial navy.”

As for Ilya Repin, his father had served in an Uhlan Regiment in the Russian army, and Repin was a graduate of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Saint Petersburg.

The Russophobia of the Met did not stop there. As Antonov’s essay notes, “Another example of ignorance by the Met is the renaming of Edgar Degas’s ‘Russian Dancers’ to ‘Dancers in Ukrainian Dress’.”

This is true. Moreover, in introducing the work the Met declared, “In 1899, Degas produced a series of compositions devoted to dancers in Ukrainian folk dress,” ignoring the fact that Degas himself named the drawings “Russian Dancers,” thereby reflecting the reality that he was devoting his drawings to dancers in Russian folk dress.

But historical accuracy is not, apparently, what the Met aspires to. As Ambassador Antonov explains, “Moreover, a comment added beneath the picture now reads: ‘The subject reflects the surge of French interest in the art and culture of Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, following France’s political alliance with that Empire in 1894’. Those who came up with this idea did not bother to figure out that it was dancers of the Russian Imperial Ballet on tour in Paris who inspired the French impressionist to create the masterpiece. It is naïve to imagine,” the Ambassador notes caustically, “that the artist was familiar with ‘the great Ukrainian choreographic school’.”

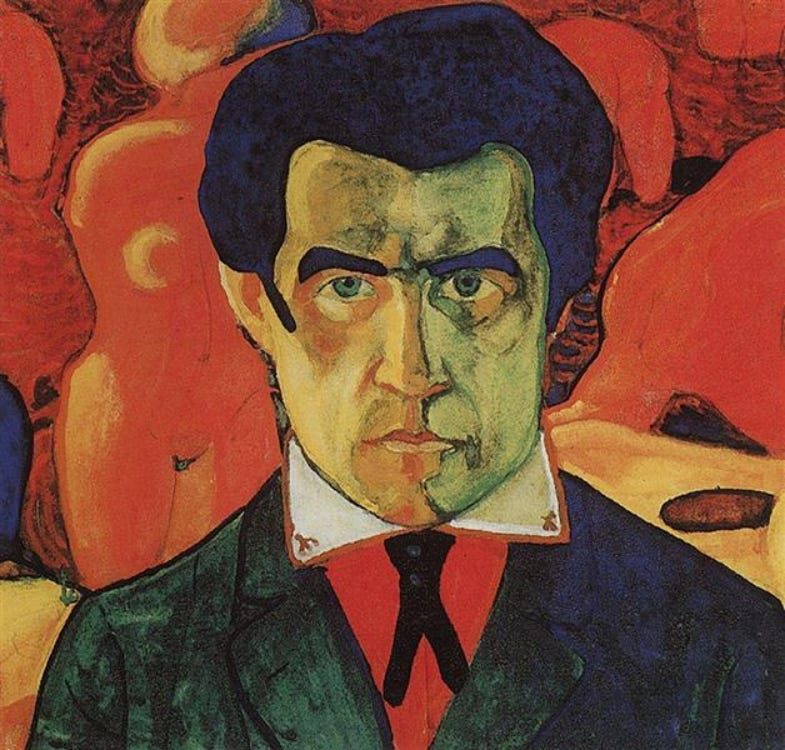

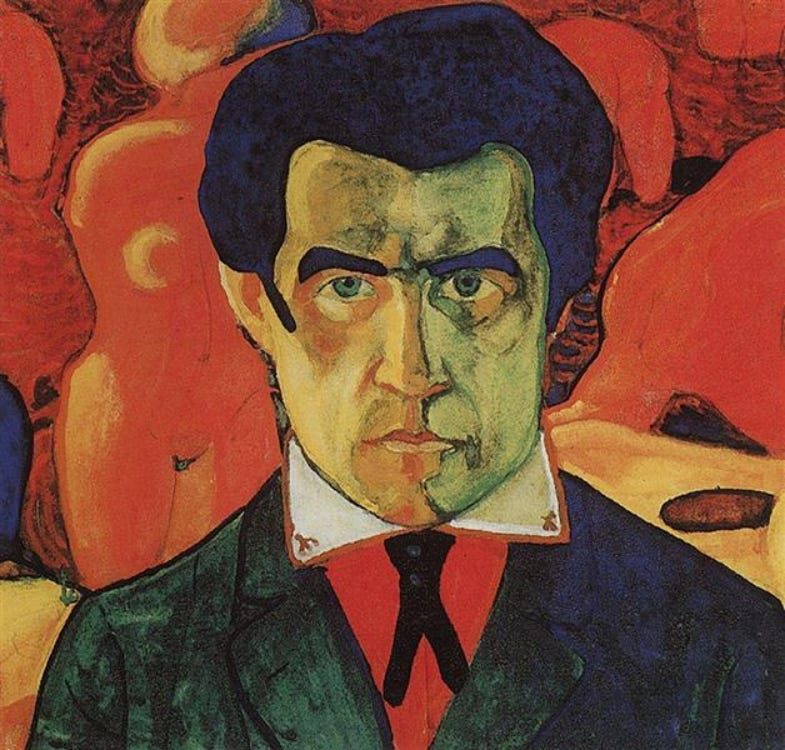

Anatoly Antonov lambasts the decisions of the Met to cancel Russian art history in the name of virtue signaling. “The American Museum of Modern Art,” his essay notes, “has also yielded to the derangement, dedicating a permanent-collection gallery to works by ‘ethnic Ukranians’. Titled ‘In Solidarity’, it features pieces by Kazimir Malevich, Leonid Berlyavsky-Nevelson, Sonia Delaunay-Terk and Ilya Kabakov.”

Kazimir Malevich was an ethnic Pole, born in Kiev in 1879, and widely considered a leading Russian avant-garde artist and art theorist. Malevich’s pioneering work had a profound influence on the development of abstract art in the 20th century. His art, and associated politics, ran afoul of Joseph Stalin, and Malevich suffered persecution at the hands of the KGB, before dying in Leningrad in 1935.

The Ukrainian art historian-turned-activist, Oksana Semenik, led an online campaign to have the Met reclassify Malevich as Ukrainian. “Russian art critics who had access to the KGB archives,” she tweeted, without referencing either the art critic or the archival material in question, “note that Malevich answered that he was Ukrainian when asked about his nationality.”

Semenik went on to tweet, “So, @MuseumModernArt, how about making corrections about his true nationality? It will be a present for his birthday (note: Malevich was born on February 23.)”

Self Portrait, 1910, Kazimir Malevich

Self Portrait, 1910, Kazimir Malevich

A modicum of due diligence, however, of the sort one would expect from an institution such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where assiduous accuracy in the pursuit of art history is the norm, not the exception, appears to be lacking in the case of Ms. Seminik.

Far from a simple art historian, Oksana Seminik is what she calls a “cultural journalist” whose articles have been published in outlets such as The New Statesman, a British progressive political and cultural magazine with a decidedly pro-Ukraine, anti-Russia editorial bias. On April 4, 2022, The New Statesman published an article authored by Oksana Seminik entitled “I escaped Russian atrocities in Bucha. My neighbors weren’t so lucky.”

The account of Ms. Seminik is what it is, and it is important to note that she provides no first-hand observations of so-called “Russian atrocities.” What is more interesting is her naming of her partner, Saskho Popenko, and the name of the person who edited and translated the article into English, Nataliya Gumenyuk. Both are journalists working for the Public Interest Journalism Lab, which in 2022 was awarded the Democracy Award from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), an erstwhile non-governmental organization formed in 1983 during the Reagan administration to assume control of CIA programs operating overseas designed to influence international public-private opinions and policies. The NED is funded by an annual grant from the United States Information Agency, and receives direct tasking from the US Congress regarding specific countries of interest to the United States. Ukraine has been designated as such a country.

In 2015, the NED was banned in Russia under a law targeting so-called “undesirable” international organizations.

It is not my position to question the motives of either Ms. Seminik, Ms. Gemenyuk, the Public Interest Journalism Lab, or the NED.

Likewise, Russian domestic policy is a matter for Russia and those impacted by it, including the NED.

However, one cannot pretend to turn a blind eye, as the Met does, to the fact that its most ardent proponent for the cultural cancellation of Russia in the Met is not a simple Ukrainian “art historian,” but rather a journalist-activist affiliated with a partisan Ukrainian organization that receives funding from a US government-controlled agency that has a chip on its shoulder against Russia for being evicted as “undesirable.”

By acting on Ms. Seminik’s passions regarding the re-classification of longstanding Russian artists as Ukrainian (something the Kiev Post has described as the “Decolonization of Ukrainian art”), the Met has allowed itself to become, wittingly or otherwise, a de facto tool of anti-Russian propaganda.

This is not the proper role of a major American cultural institution.

Here I will let the anger and frustration of the Russian Ambassador to the United States to manifest itself without comment:

Judging by the rhetoric of the American art beau monde, Vasily Kandinsky, a native of Moscow, and his works are next in line to be ‘ukrainized’. There is a heated discussion on whether the fact that he studied in Odessa is a good reason to treat him as a Ukrainian artist.

Here arises the question for the museum innovators who until recently admired Russian culture: why they has set about perverting historical reality only now? Isn’t this sudden “revelation” just a banal tribute to political fashion? Anyway, the time will come for the US cultural elite to sober up and be embarrassed of its doings.

Perhaps. But the reality is that what passes for culture today in America is anything but, especially when it comes to all things Russia. Liquor stores have poured “Russian” vodka out in protest of the Russian military incursion into Ukraine, ignorant of the fact that many of the brands they were disposing of originated from places other than Russia.

Town officials in Hempstead, Long Island, pour out Vodka in protest against Russia

Town officials in Hempstead, Long Island, pour out Vodka in protest against Russia

Other absurdities abound. The Miri Vanna, a well-known Washington, DC-based Russian restaurant, has renamed the famous “Moscow Mule” mixed drink (two parts vodka, three parts ginger ale, and a squeeze of lime juice) has become the “Kyiv Mule,” and the long-time Russian staple, borscht, has been redefined as “the masterpiece of Ukrainian cuisine.”

But the culture war against all things Russian has serious connotations as well. The Russia House, an established Washington, DC-based Russian restaurant, was vandalized in the weeks following the Russian incursion into Ukraine, leading the owners to shutter their doors for good (the restaurant, like many others, had temporarily closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.)

In New York City, the iconic Russian Samovar restaurant came under attack simply because of its name, forcing the owners to fly Ukrainian flags and profess their open support for Ukraine, lest they, too, be subject to attacks that would derail their business.

It is not just Russian culture that is being cancelled in the United States, but Russian people, including those dispatched to the United States by the Russian government for the singular task of improving relations between the two countries. A recent exposé published in Politico, entitled “Lonely Anatoly: The Russian ambassador is Washington’s least popular man,” observes that “Russia’s ambassador to the United States can’t get meetings with senior officials at the White House or the State Department. He can’t convince US lawmakers to see him, much less take a photo. It’s the rare American think tanker who’s willing to admit to having any contact with the envoy.”

Ambassador Antonov is not the only Russian official singled out for diplomatic isolation. In March 2022, at the request of the Ukrainian embassy’s defense attaché, the Canadian Embassy orchestrated a vote by the Defense Attachés’ Association, a professional and social organization for defense attachés and their spouses whose dean is selected by the Defense Intelligence Agency, to expel Major General Evgeny Bobkin, the Russian Military Attaché assigned to the Russian Embassy in Washington, DC, from the group.

“It was hard to believe that xenophobia could take roots,” Ambassador Antonov observed, “in a state which is supposed to be resting on the principles of cultural and ethnical diversity and tolerance to different peoples. Nevertheless, US politicians not only encourage hatred of everything Russian, but actively implant it in the minds of citizens. In recent years, they have never stopped fabricating baseless accusations to justify tougher sanctions.”

One of the problems confronting the Russian government and people today is the quality of individuals that comprise what passes for “Russia experts” in America today. Gone are the days when men such as Jack Matlock, the former US Ambassador to Russia, or Stephen Cohen, the deceased Professor Emeritus of Russian and Slavic Studies who taught at Columbia, Princeton, and New York University, dominated the halls of academia and power. Both men possessed a deep appreciation of Russian history, culture, traditions, language, and politics. Erudite and tough, they articulated for better relations between Russia and the United States.

Today, they have been replaced by people like Michael McFaul, the former US Ambassador to Russia under Barack Obama, and Fiona Hill, a National Security Council “expert” on Russia in both the Obama and Trump White Houses. Both McFaul and Hill have expressed a Putin-centric approach when assessing Russia, where everything is explained through an incomplete and narrowly focused concentration on the Russian leader over the Russian nation.

The contrast between the approaches taken by Jack Matlock and Stephen Cohen, on the one hand, and Michael McFaul and Fiona Hill, on the other, could not be more stark; the first argued for bridging the differences through better understanding, and the other for managing differences through containment and isolation.

One promotes peaceful coexistence based upon principles of shared humanity.

The other promotes never-ending conflict fueled by Russophobia.

“Russian culture,” Ambassador Antonov concludes, “does not belong only to Russia. It is the world’s treasure. We know the Americans as appreciative connoisseurs of true art. Not so long ago tours of the troupes of the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theatres as well as our renowned musicians drew packed houses and were always greeted with a storm of applause. The local audience is apparently longing for Russian performers and art exhibitions.”

“Isn’t it time to stop the Russophobic madness?,” the Russian Ambassador asks.

That, I believe, is the question that defines our times, and our collective fate.

Who among us will be the next Van Cliburn? Who will challenge the modern McCarthyism by refusing to bow to the insane pressures of Russophobia, and decide instead to engage with the Russian people as people, with full respect and admiration for their culture, heritage, traditions, and history? This journey doesn’t require a trip to Moscow. Defeating Russophobia begins here at home, simply by choosing not to buy in to the madness promulgated on the part of those who seek to promote conflict by promoting fear generated by ignorance.

When it comes to stopping the madness of Russophobia, there is no time like the present. Because if we allow fear-based prejudice to prevail, there may be no tomorrow.

The Red Scare and McCarthyism (1984), Judith Baca

The Red Scare and McCarthyism (1984), Judith Baca Van Cliburn performs at the first International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition, 1958.

Van Cliburn performs at the first International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition, 1958. The Wave (1889), Ivan Aivazovsky

The Wave (1889), Ivan Aivazovsky Self Portrait, 1910, Kazimir Malevich

Self Portrait, 1910, Kazimir Malevich Town officials in Hempstead, Long Island, pour out Vodka in protest against Russia

Town officials in Hempstead, Long Island, pour out Vodka in protest against Russia