The Anti-Empire Project

[Following up the previous articles on nonviolence with this transcription of a discussion on The East is a Podcast, from 2021 inspired by Marcie Smith’s articles on Gene Sharp.]

[Following up the previous articles on nonviolence with this transcription of a discussion on The East is a Podcast, from 2021 inspired by Marcie Smith’s articles on Gene Sharp.]

Justin Podur: I’m here to discuss nonviolence with the panelists Sina Rahmani and Zeyad Nabulsy. And I wanted to start with the philosophical. And Zeyad is kind of a philosophical person who’s here.

Zeyad Nabulsy: Okay, I’ll introduce myself. I’m Zeyad and most of my research is on modern African intellectual history including African philosophy and history of science.

Justin Podur: It was your idea to discuss nonviolence.

Zeyad Nabulsy: I think in terms of the philosophical angle. So, so here is one way to explain why nonviolence is prevalent as a kind of trope that gets invoked in a lot of contemporary political discourse and in a lot of contemporary moral discourse. So think of like somebody who’s a Kantian, if you look at a certain approach to moral philosophy, it’s saying, okay, look, the world is a horrible place, basically, and I want to get out of this world with my hands as clean as possible. I think that’s more or less an accurate gloss of like what a Kantian would think. Once you have that point of view, I think then it becomes about fetishizing things like non-violence, fetishizing non-violence, and it becomes sort of a normative debate about what is right and wrong from a moral standpoint. And it’s not that these debates are not important, but I think when we’re talking about politics we’re talking about what is also efficacious, because sometimes the way people talk about this, they say something like violence never works, which, as a descriptive claim, is utterly false. So I that that’s where I think we should focus. That’s my view.

Justin Podur: So, normative. You mean, how one should behave?

Zeyad Nabulsy: Yes, precisely.

Justin Podur: So if you want to make the world a better place, you shouldn’t do violence. That kind of idea, because violence hurts the person you’re doing violence to.

Zeyad Nabulsy: Right. And it hurts you. So some people say, it dehumanizes you.

Justin Podur: Is that true?

Zeyad Nabulsy: Here’s the problem. I think the normative or moral standpoint becomes very inadequate for actually understanding concrete political issues. Under what conditions is violence acceptable? We don’t actually discuss any concrete case studies. So Palestine will be one of our central case studies. So my inclination is to think about how do these organizations work? What is efficacious? I know that sounds sort of Machiavellian, and it is. But I think that’s also like an element of Marxism is to, like, reject this moralistic, normative discourse.

Justin Podur: I’m all for moralistic discourse. I am. I think it’s a great thing to do to figure out how to be a good person and what what to do to be a good person in the world. You can build that abstract kind of house out of a series of premises. But when you get into a concrete political situation, then you have many, many, many more variables. And then to say that if someone is trying to kill you, if someone is doing Machiavellian, cold blooded politics against you, for you to say, I’m not going to do that in return, that could be immoral. You could be enabling something worse. So there are norms that work in simple situations or laboratory situations that don’t translate to the real world. So maybe that’s reason enough to reject starting from a normative perspective. I don’t know, are nonviolent people better people?

Sina Rahmani: This is bullshit. This is all bullshit. Like this entire idea, the world is this infinitely diverse place full of thousands of years of civilizational violence and and terror. The idea that you can break off history at a nice fictional point and say, oh, from now on, we do no violence. It’s a stupid liberal idea that ultimately says more about the discourse itself and the people who are trapped in it, i.e. all of us. Because once again, we have to realize that, like we talk about politics, we actually live in extremely depoliticized societies. All of us, especially in the English speaking world at least, whereby corporate media and the cultural wars that are curated by corporate media in alliance with academia curate a set of talking points for every semester, all pre-prepared. There’s a very small agenda of what gets discussed and it’s all done within this tiny bandwidth or narrow spectrum of this option. So all of this entire discourse is itself false, because what we’re doing is just doing political theory. The political theory of what is good and what is bad, which is totally stupid. And especially when it comes to the question of violence. A definition of violence is the guy with a Kalashnikov and a Keffiyeh as if that’s the only form of political violence, as if there isn’t political violence unfolding every day in late capitalist society everywhere. And it’s class and it’s race and it’s gendered, and it’s got all kinds of all kinds of complications and nuances based on the social context. And so the very idea that we can speak in theoretical terms, global theoretical terms about a stupid fake thing called nonviolence, it’s one of the one of the weird things that we absorbed as radicalism, which is sold to us as radicalism. So like WTO protest and all that stuff that the Gen X kids did. My contention is that this is just this is the conversation itself is false. But we should read this article.

Justin Podur: To skip ahead to the conclusion of this whole discussion from my perspective, is that the entire dichotomy is fake. The debate is fake, the dichotomy is fake. There’s no meaningful way to debate violence versus nonviolence in politics.

Sina Rahmani: It’s all a big red herring conversation.

Justin Podur: Violence. There’s no nonviolence. Both are always present. To divide it artificially into one and the other, it’s like, I can’t think of a great analogy. I’ve been thinking about analogies, and I think it’s like, imagine dividing fighting into punches with your right hand and punches with your left hand, and saying punches with your left hand are off limits, but punches with your right hand are are fine. You create this taboo when there’s no meaningful difference between those two things.

Zeyad Nabulsy: And can I just add something with that analogy? You’re banning using your left hand only on one side. So it’s asymmetric. That’s very important because your opponent doesn’t care. They’re like, okay, you’re an idiot, then I’m going to take advantage of it. Thank you.

Sina Rahmani: It’s a symptom of the fact that our depoliticized era is trapped under this stupid memorial rubble of World War two, the defeat of the Nazis and the rise of American Pax Americana as some kind of end of epoch in human history. Nonviolence and the institutionalization of it through activists and through the work of Gene Sharp, specifically the the presentation of the Third Reich as the antithesis to liberalism itself, with its with its weird, diabolical cousin, communism. Both of these are two wings of authoritarian politics that were thorough handedly defeated by liberalism in 1991, such that mediocre neocon philosophers were announcing the end of history.

Justin Podur: Let’s take it back to Domenico Losurdo’s book about nonviolence. Losurdo is a philosopher. But great history. He wrote The Counter History of Liberalism, which I would highly recommend to everybody. And then he has this book about nonviolence. And a lot of it’s got Gandhi, but the the chronological thing that he starts with is the so-called non resistors. So there were these abolitionists, white abolitionists, Christian religious people who were against slavery in the mid 19th century. You know, it’s from 1808 when when Britain, stopped the slave trade, they were pushing for abolition in America. And these people were they were very, very specific that they did not support any slaves uprising. So they were very careful. They broadcast that from everywhere. They were like, we don’t want slaves to take up arms. We don’t want slaves to rise up. Slaves should suffer and show their by their suffering that they’re human beings, Christians, etc and Losurdo talks about what happened in the 1840s. There were these thousands of riots, most of them against abolitionists, lots of them to do with politics and elections and stuff. And some of these some of these white abolitionists were lynched. They were killed by pro-slavery people. And he kind of tracks some of these non-resistance people. And the changes in their views as more and more of them are getting killed by pro-slavery and they gradually start at least supporting some kind of defensive violence, at least for themselves. They may not support a slave revolt, but they start saying, well, these people are, you know, we’re against violence, against human beings, but these are not human beings. William Lloyd Garrison being the the biggest example of this. Of course, there were black abolitionists like the people described in a book called Force and Freedom who were always about armed abolition, and John Brown put an end to the debate. He was like, “yeah, we’re not going to have this nonviolence debate anymore.” And, you know, so that that kind of was the closing of that chapter of nonviolence.

Sina Rahmani: But then they had an entire war about slavery. That’s how much nonviolence means to the United States. They had a full scale war across the entirety of their country.

Justin Podur: You know Brown wanted to start that war sooner, right? Brown was like, “we need to get this war going.” And a lot of his abolitionist Christian comrades were like, no, we we can’t have slaves, doing violence. That would be violence, right? And Brown just wasn’t having it. He didn’t win that debate at the debating society. But he did win it.

So the next time we pick up the nonviolence thread in terms of global movements is Gandhi. And Losurdo talks about how Gandhi wants organized medics, medical brigades to fight for the British in World War One. And his whole thing was like, we don’t have to shoot or kill people, but we can show how courageous we are on the battlefield. And by showing that we are real men, we could convince the British to let us free, give us freedom. Losurdo says that it’s more about co-optation than nonviolence than nonviolent resistance. There’s a whole discussion worth having about what the difference is.

So now we’re into modes of resistance. So if we’re talking about resistance we’re talking about trying to fight back. And, you have Gandhi, you have Martin Luther King a little bit later. And these people are talking about fighting back. So how about how about the efficacy of nonviolent resistance?

Zeyad Nabulsy: We can’t really discuss efficacy without talking about context. So global context is one factor. So for example in evaluating the success or failures of Gandhi, the movement for independence in India, you have to look at the global context. You have to look at like the internal balance of power. But people just want to talk abstractly how “nonviolence works”. Maybe under some circumstances it does. Other circumstances, it simply doesn’t. I’ll give you an example where it didn’t: in the 50s, the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde), the party which liberated Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde eventually from Portuguese rule, at first they tried having, peaceful worker strikes and so on. In 1959 [note: the Pijiguiti massacre in Port of Bissau, August 3, 1959] there was this massive massacre, basically the Portuguese just shot the protesters. And after that they turn towards a people’s guerrilla war because it’s clear in this context that the Portuguese will not give up without a struggle. And there is a political economy explanation for that. Because Portugal was so weak as an economic power, it couldn’t have a neocolonial relationship with its African colonies. It’s not like France, not like Britain. So after the Portuguese left they were not the main neocolonial power in either Guinea-Bissau or Cape Verde or even Angola. That’s why I think the history itself is very important beyond just the normative philosophical debates about “is nonviolence good or bad?” They’ve been given an outsized importance.

Sina Rahmani: In 2021, the idea that you can confront some of the most powerful police institutions, instruments of state violence, most advanced in the world are deployed on any population. Modern police is two centuries old. It developed in the colonial setting. The very fact that we can even be at this point where where the tiny, irrelevant class of eggheads and liberals and writers and journalists and all of their hangers on, the tiny class of them, circulate position papers around this abstract topic as if it means anything to anyone. It’s more of a reflection of the poverty of our discourse. Our understanding of politics is so juvenile that we could even entertain this logic, that if you just protest enough, the state will change its mind, because that’s how democracy works. This is not how states work.

Justin Podur: We have Gandhi and Gandhi’s got a really interesting history because he joins the Congress when the Congress is really like a loyal opposition talk shop. So they’re just talking, right? They’re signing petitions, they’re writing letters. It really is a cooptation machine. And Gandhi gets them into so-called organizing, mobilization, mass mobilizations. He involves millions of people. That’s a whole other level above what they were doing. Right? But there is another history of the Independence movement, outside the Congress Party, over the decades that Gandhi was involved. And I have yet to study this properly. I have been trying to find sources. It’s hard to find sources. But there was lots of terrorism. There was lots of bomb throwing. There was lots of violence. I mean I’ve talked about 1857. I’m trying to sort out what was going on prior to Indian independence in the decades before. There was Bhagat Singh, who threw a bomb and was hanged. There were lots of people who were hanged. During World War two, there was the Indian National Army of Subhash Bose, who was trained by the Japanese.It was a sign to the British that he was able to recruit and organize an actual military invasion of India. There was apparently a mutiny in 1946 of sailors in India.

So the writing on the wall in terms of violence was also going on. And there’s also critiques of Gandhi by people like Ambedkar, who was one of the leaders of the untouchables, who was saying… Gandhi would go on a fast to try to coerce untouchables not to seek certain affirmative action type provisions in the law. And Ambedkar had this thing where he was like: that’s great, Gandhi, that’s so great that you’ve chosen this non-coercive method of, non-violent coercion against me and the untouchable community. So what happens if you finish your fast and die of hunger on your hunger strike? Do you think that all of your gentle, kind supporters will not be enacting reprisals against the untouchable community? Because I sure think they will. I sure think this this non coercion threat is actually a massive gun pointed at the head of our community if you die.

On the Martin Luther King front, there’s a book called Negroes with Guns. There’s a book called We Will Shoot Back. There’s another one called This Non-Violent Stuff Will Get You Killed. They talk about how many of these Martin Luther King followers were actually armed and walked around armed because they’re like, are you crazy? Of course I’m armed, you know? But so for them, nonviolence was not a way of life. It was a very specific tactical choice.

Sina Rahmani: We know so little about the outside world that we could go so far and tell things to other people that, oh, this kind of politics is bad. This kind of politics is good. But of course, what we are doing is reacting to the media we consume. Right? Which is itself ridiculous. No, you’re not talking about world politics. You’re talking about the thing you saw on the nightly news broadcast.

Justin Podur: So fraudulent liberals in the US, these non resisters were saying it’s wrong to do violence to try to change slavery. But they’re not counting the lashes, right? Like every lash. You would think that every lash that takes place in the field to get somebody to speed up their cotton harvesting, you would think that would be considered violence, because if someone’s lashing a white person, that sure as hell counts as violence, right? Does daily violence count?

Zeyad Nabulsy: Does it count? I was reading this this book, it’s sort of like an oral history of Nasserism, in Arabic. He talks about these villages in Upper Egypt or southern Egypt where up until like the 50s if you’re like a regular peasant or something, if you’re walking and you see one of the notables of the town, you have to dismount, you bow down. That’s a form of violence!

Justin Podur: Of course it is. What if you don’t do that? What if you are walking along and don’t do that? What will happen to you if you don’t do that?

Zeyad Nabulsy: Imagine you’re a dad with your kids and then you have to grovel in front of this guy, just like on a daily basis. But this violence is rendered invisible.

Justin Podur: Okay, so when you first brought up the idea of doing an episode on nonviolence, I immediately thought of this two part article by Marcie Smith on the non-site dot org (part 1, part 2). And it’s about Gene Sharp. And Gene Sharp is what Marcie Smith describes as a defense intellectual. He worked at Harvard his whole life, starting in the 50s. And there’s a whole ideology, a really well developed ideology from the 1950s on that Gene Sharp takes up. He calls his institute the Albert Einstein Institute. He gets some kind of early endorsement from Einstein, and he takes up these symbols: Gandhi, Martin Luther King, these different nonviolent icons. But he develops a whole system. The ideological system is: the contradiction in the world is between violence and nonviolence. Violence is when you impose your will on someone else, when you do harm, to impose your will on someone else. And out in the world, the people that are doing this the most are states, regardless of their political orientation. Nation states are doing violence to people every day. And the way to combat this violence is by overthrowing these states in a nonviolent way, through non-revolutionary nonviolence.

So under this rubric of revolutionary nonviolence, there’s a whole playbook of 198 tactics to undermine the legitimacy of the regime. You go and you get beaten up before the cameras to show the regime no longer has legitimacy. You involve more and more people because it’s nonviolent. So more people can, in theory, get involved than if it was a violent struggle where it biases it towards men. They do training in, in nonviolent skills. And we’ll get to like the effect on the American movement first next. But one important premise in Gene-Sharpism is: the contradiction is not class, okay? The contradiction is violence and nonviolence. It’s states. It’s dictatorship versus something called authoritarianism.

Sina Rahmani: Stupidest fucking premise in the world. It’s such a liberal view of the world, a bourgeois liberal. Exactly what Marx talks about: this bourgeois reification of the world as located in this private individual, circulating freely as a commodity, as an object of the market, and subject to the rules of some kind of agreement or like whatever social contract with the state.

Justin Podur: And Smith also puts it in a Cold War context where because there’s this danger of nuclear war with the Soviet Union at any point and because there’s McCarthyism, so you can’t be a communist in the US. The result is that to make an assault against these communist regimes, the US is very interested in nonviolent organization and nonviolent movements that are not going to escalate into war, but they’re still trying to overthrow the regimes. They’re trying to take away the ability of communist states to do both good things and bad things, destroy the whole state.

Zeyad Nabulsy: The authoritarian non-authoritarian taxonomy is very interesting because this is such an abstract way of thinking about these things. People don’t think of the US as an authoritarian state. For example a black kid in some like heavily policed inner city area – for you, the US is an authoritarian state. Of course, I’m the cop, you know, like walk by something. He makes you stand there for three hours or something just to humiliate you, maybe physically beats you. So it’s always the question of where in the state is authority being used and the threat of violence is being invoked, and against whose interests and for whose interests.

Justin Podur: Us have concentration camps? Yes. The US have prison camps.

Sina Rahmani: The US has prison camps. Slave labor. But the US isn’t authoritarian because I can tell Trump to fuck off. As if that is the beginning and end point of political subjectivity. And then on top of that, the US is also the source of the world’s most nasty “revolutionaries”. So in the case of all those regime change operations that will probably get to in this conversation, those people are “revolutionaries” and the US supports them. So on the one hand, the US fights its own revolutionaries with the most violent political, legal, juridical police force that’s ever been enacted. Like if you do anything against the state in your court in this country, you are going to jail for decades, and maybe you can get five years off if you rat on all your friends and they will hammer you and they will destroy your family’s finances, your finances, your name. They’re so authoritarian. They go and fish for collaborators and get people to offer things. They conduct political assassinations, like against the Black Panthers. I remember there’s some neocon critic, some general who was critical of the neocons. He died of a heart attack. Gee, I wonder. And then this is the liberal viewpoint that no, I am civilized subject. I’m a subject, a modern subject of a civilized liberal state and enshrined in the legal fictions of all.

Zeyad Nabulsy: The funny point about this liberal approach is it’s almost like there is this idea that there is an interiority that’s not expressed in your actions. So you could have a history of like murdering people for 150 years. But you’re not a murderer. It’s what you are inside that counts. It’s this essence that never expresses itself in action. It’s hidden somewhere.

Sina Rahmani: Sharp was working directly with the American deep State. Yeah. The idea that you can have transformational change in the state apparatuses or plural of them, whatever you want to call them, that, that can take some sort of radical form like, and the symbols that we recognize to this day, like the raised fist and all that stuff, like, I mean, that has its own weird history too, right? Because it was appropriated from the Panthers. There’s probably a deeper story, probably. But like that image, though, the image of radicalism as a performance. It’s a performance.

Understanding that in how many examples could we start at the top of our head? Ukraine? How obvious is it to say what happened in Ukraine? Was this colour revolution that that the US has more or less admitted? I mean, that’s the thing, like with all these fucking deep state operations or whatever, like it’s not even like we’re the tinfoil hat. They admit to this stuff. They’re happy to because of course, the Empire, this is all in pursuit of the Empire. And fundamentally, most Americans either don’t care or approve of their empire’s actions because they implicitly understand. And this is what they realise is one of the few things they actually understand about politics, that the comforts of their lives are built directly upon the exploitation of the global South.

Justin Podur: In Sharp’s ideology, exploitation is not violence. Okay, so capitalism is not violence. All the profit and paying someone peanuts. That’s not violence, right? Campaigning non-violently to lower the minimum wage is not violence.

So everybody heard about the color revolutions. And a lot of I think conspiracy people are like, this is George Soros behind it. But George Soros may be funding these kinds of operations, but the thinking, the playbook is not conspiratorial. It’s called Strategy for a Living Revolution. And it’s a book and it’s translated. Just read it. He tells you what they’re doing.

Sina Rahmani: All of this is to say that the things that we recognized and are represented to us as revolutions fit this mold, and the ones that don’t trouble us and need to be turned back.

Justin Podur: So Hong Kong, the Arab Spring, even the Tiananmen Square movement had Gene Sharp fingerprints on it.

Sina Rahmani: Libya, Ukraine, Egypt, Egypt. Like they were getting that money, too, right? And they came out against Mubarak, their own ally. They were feeding the enemies of their own ally. This training, this cookie cutter training. They had their own satellite phones. It’s a playbook. And there’s literally an author to it. And they published it.

Zeyad Nabulsy: So it’s not even a conspiratorial thing. I just want to go back to Justin’s point about like whether exploitation is violent or not. And I think it’s not even that we have to say that exploitation is violent. But why is exploitation, a thing which might lead to massive violence or presupposes massive violence, not important for somebody like Gene Sharp?

Justin Podur: And it’s like you were saying, the threat of violence is is what underlines the whole thing. You want to find out if you if you live in a non-violent society, try to organize a union at your workplace. And tell your boss. Hey, boss, we’re a union now and we demand a raise. See what happens. So tell your boss we’re now taking over decision making in terms of investments. See what happens to you. See how that works for you, right? Any institution you’re in? It depends on the threat of violence.

Zeyad Nabulsy: And I think the point about action is really important because you could have a society that’s authoritarian, that allows some kind of freedom of expression, but doesn’t allow you to organize freely because that’s really the significant threat.

Sina Rahmani: Scream all you want about it. Nothing will change. If that doesn’t summarize American life, that they can’t even get basic health care. Like the country that crows about human rights all around the world that has a whole class of people, a diverse Benetton ad class of people, professionals who themselves identify as human rights professionals. And they’re a product of a culture that doesn’t even feed its own citizens properly. It’s a failed state, and it’s designed to be a failed state.

Justin Podur: We have gun rights in America. Do Black people have gun rights in America? Did Philando Castile not get shot for having a gun, by a police officer?

Sina Rahmani: It’s all so insulting that as if the violence of everyday life, the class racialized gendered like across these multiple axes of power and privilege and how society values certain lives and disowns others figuratively and literally, the fact that we can’t even articulate them, and instead we have these asinine conversations about other countries and then deem them to be good or bad. And then meanwhile, our state, our own state apparatus are supporting the most violent forces that ever existed, reactionaries that would never succeed by any liberal test. Like all the US academics who promoted the the proxy war on Syria as some kind of liberation, as if they would even be in the same room as some FSA people.

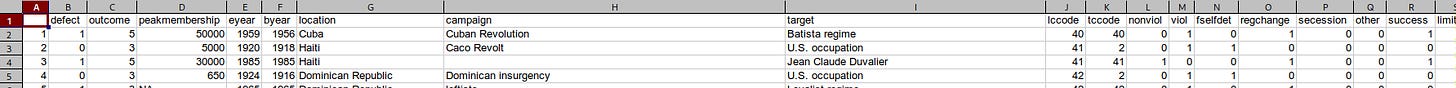

Justin Podur: But listen, George Lakey is the protege of Gene Sharp, that brings nonviolent revolution to America in a big way and through various movements. There’s a great letter in this Marcie Smith article by a guy who left the nonviolence movement. And he became a Marxist, and he explained why he doesn’t buy this Gene Sharpism anymore. So Lakey’s ideology, which gets into the Ruckus Society, which gets into Central America, gets into the Battle of Seattle, the anti-globalization movement. It’s full of nonviolence. So imposing your will on other people is nonviolent is violence. Hierarchy is violence. So you construct your movement out of affinity groups, and decision making is done by consensus. There’s no hierarchy, there’s no leadership, there’s diversity of tactics. And they do these trainings, nonviolence trainings. It’s always nonviolence training and skills. And they’re everywhere. And then there’s an academic component, there’s academics who wrote this quantitative study called Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolence. So they classified all these movements, hundreds of movements across the world, and they rated them as a “1” if they succeeded. If they didn’t succeed, they got a “0”. And it turns out that you’re twice as likely to succeed if you’re nonviolent than if you are violent! These are the numbers. The numbers don’t lie. So he brings it home.

There was a debate that I watched just before during the anti-globalization movement between Ward Churchill and George Lakey – violence, nonviolence. And unfortunately, Churchill said some of the stuff we’re saying here. Lakey said if you have a violent strategy, I’d like to hear it. And he laid out his nonviolent strategy for revolution. So it was kind of like a vacuum thing, right?

Because anti-communism clears out anything that smacks of Leninism. Build a party, build unions. Organize the people, arm the people, take over, make change. That’s what the different communist parties do. So that’s not allowed. You can’t even talk about that because of McCarthyism. So now there’s this vacuum. And then here comes Sharp and Lakey with revolutionary nonviolence, affinity groups, freedom, overthrow the state, attack its legitimacy, overthrow it and keep overthrowing it until something good happens. Right?

Zeyad Nabulsy: A game of chance, until you get a good hand.

Justin Podur: But ultimately, here’s the thing. Because I read Why Civil Resistance Works. And I looked at the data, they published their, their data set, and I tried to do some analysis of their data. And it’s interesting how you code it, right? How you code it, because I think the First Intifada in Palestine was coded as a success.

Sina Rahmani: What are they fucking talking about? American academics are so stupid.

Sina Rahmani: What are they fucking talking about? American academics are so stupid.

Justin Podur: Where I’m going is this: I think that the Palestinians are the ultimate target of this whole thing.

Sina Rahmani: The US is the ultimate target.

Justin Podur: No, I don’t think so. I think the whole thing is leading to, why can’t Palestinians be nonviolent? And if you think about it, Finkelstein wrote a book about this too. Finkelstein wrote a book called What Gandhi Says.

Sina Rahmani Shut up.

Justin Podur: He read thousands of pages of Gandhi’s writings, he wrote a book about what Gandhi actually says. So he creates these tables about what Gandhi says. And he was like, I studied Gandhi because I wanted to know about the efficacy of nonviolence for the Palestinian movement. And during the brief war on Gaza in 2021, Finkelstein was in an interview, I think, on The Katie Halper Show. And he was like, I’m really sad about this because I think it’s going to discredit nonviolence.

Zeyad Nabulsy: I just pulled it up on my phone because I wanted to get the dates. Right. So if you look at the nonviolent marches in Gaza, right? March 2018. Palestinians were being shot down, and what were these nonviolence people doing?

Sina Rahmani: Collecting checks as professionals of nonviolence.

Zeyad Nabulsy: At the performative level, they remember that nonviolence is actually important to them when Palestinians fire back, when they do violence. But otherwise they have this amnesia. They’re like, oh, I don’t know, violence, non-violence. I have no idea. Honestly, it’s not even a serious project.

Justin Podur: That’s exactly what what Finkelstein said. He said, look, people, you know, Hamas people have said, we tried nonviolence in 2018. And I just think it’s a shame because now they’re going to think that violence…

Zeyad Nabulsy: …and they would be right to think that. Any rational human being faced with these circumstances would arrive at that conclusion. It’s not some crazy, fanatical thing. It’s like, okay, we tried this.

Sina Rahmani: It’s an irrelevant thing for us to even think about. The location of our critique in this conversation is always extraterritorial. his is what it’s like from outside, based in the most violent society ever to have existed, that sits atop a mountain of indigenous people’s skulls and bones.Every day that we’re digging up their children that we eradicated in schools. And then we have the audacity to sell this. The fundamental, profound, blood stained legacy of the supposed European enlightenment, as if it is ever something that could ever be even discussed, as nonviolent, as if the French Revolution was some nonviolent thing. Are you kidding me? The guillotine memes that still circulate. Politics is violence, and revolutionary violence is part of any political struggle. If it was a real struggle to overturn something important enough that somebody would fight back. If something was so easy to throw over, you could just bring out a bunch of corny ass placards and perform for the camera so you can get 30 seconds of airtime in the Buffalo fucking NBC affiliate. That’s this is about how we consume the world.

Zeyad Nabulsy: If you look at historically when Israel has made concessions, it’s always sort of in the aftermath of a war when you inflicted material damage on them or you made them think, okay, actually, we could get screwed over here. That’s it. There is no other path to success with Israel.

Justin Podur: Revolutionary nonviolence does not say we move their conscience. They attacked the regime’s legitimacy.

Sina Rahmani: Legitimacy to what audience?

Justin Podur: Orwell talks about why Gandhi worked on the British because the British have a free press. And Gandhi wouldn’t have worked on the Nazis because they were more authoritarian.

Sina Rahmani: Blah blah.

Justin Podur: So I’ve gone to nonviolence trainings. You know, when I was in the protests in Quebec City in 2000 and April 2001. April. So before September 2001. There were nonviolence trainings by people who came up from the US like trained types. The international solidarity movement that was doing nonviolence in solidarity with Palestinians. I did that in 2002. And occupy was nonviolence, too, in 2010. I was already kind of aged out. I didn’t do very much with occupy in 2010. But I did go, I visited occupy a few times. They did all those nonviolence things, the consensus process. It’s criticized by Marcie Smith in her article too. The insistence on consensus actually makes it very difficult to get anything done. It gives everybody a veto, including people who want to sabotage your your thing. And so there’s all kinds of underhanded things, I suppose, that people do to make sure that, you know, they don’t get consensus blocked. But if you’re not sophisticated enough to do that…

Zeyad Nabulsy: Can we say something like briefly about the global effects of that? Because I think one of the global effects is it’s basically hollowed out all of these historically radical parties and various parts in the global South and turned them into activists who go attend workshops. You see that in every like Communist party, in every country in the world, now I’m working for this NGO. So it has this very pernicious effect globally.

Sina Rahmani: They manufacture a class of people who have an inordinate amount of discursive power to set a kind of media agenda.

Zeyad Nabulsy: Yeah, it’s like a managerial class for politics, basically political activism. Instead of, you know, you work in a bank or something, you’re some human rights activist.

Justin Podur: You’re an organizer.

Sina Rahmani: Never trust anyone who has human rights in their professional biography.

Zeyad Nabulsy: I think that sage advice.

Sina Rahmani: Is that a good way to end this episode?

The Myth That India’s Freedom Was Won Nonviolently is Holding Back Progress